Memories of a family living in Coombe Keynes from 1933 to 1967

By Michael Drew

I come from a long line of Dorset folk on both sides of the family. The Drews were in business and farming in Wareham and tied up with the paddle steamers and sailing ships in Weymouth. My father John was a farm student at Newburg Winfrith and married Esther Spicer, seventh child of James Spicer of Bovington farm.

They set up farming at Godlingston, Swanage in about 1916, and raised seven children there. I was seventh, born in 1928.

Due to poor health and the 1930’s Depression, Father had to give up farming and we moved to Coombe Keynes Vicarage in 1933, on my 5th birthday.

COOMBE KEYNES 1933

Coombe was very much a working village, just two farms, workers’ cottages, and a run-down vicarage, owned somewhat reluctantly by the Church Commissioners. There was no electricity or telephone, no shop and no pub. The nearest “Pictures” (cinema) was at Wareham or Dorchester . A herd of cows passed twice daily through the centre of the village between field and dairy, leaving a good supply of cow-dung on the road, and nobody cleaned it up. There was a small pond, or large puddle on the South side of the road.

Most of the cottages had a single living/kitchen/dining room downstairs; no running water, lavatory or bath; one bedroom upstairs, probably with one double bed, with the children sharing the bed or sleeping under it. The lavatories were in the allotments , one per house, in a communal building, sharing a common cesspit. A portable bath and washing basins would be stowed in an out-house. These cottages would have been tied to a farm for the use of farm labourers only.

The water came from a single communal tap on the village green (it is still there in 2014!). The dairy, farms, and vicarage had their own water supply.

Just outside the village, off Newtown Road, was a brickyard set in a clay quarry and run by the Cobb family. There was also a lime kiln built into the side of a hill at the junction of the road to Wool and the lane to Burton Cross.

Grocery services were provided and delivered by the Williams bakery family from Wool. A butcher called twice a week. In the summer a Walls ice cream man with a “Stop me and buy one” ice box on a bicycle came by and sold penny ice lollies.

A public bus service ran between Bovington and Lulworth Cove, providing an essential link to Wool station. The only car owners were the two farmers and my family. Not every household owned a bicycle.

The first shop was started in about 1934 by Mrs. Brown, who lived in the cottage attached to West Farm, and its kitchen window opened out onto the road at the sharp bend in the road. Customers would bang on the window, through which all sales were conducted. She was sufficiently successful that later she built a wooden house to the East of the village, with a dedicated shop in it. The house lasted until the 1970s, when it was replaced by the existing brick house. Her husband, Fred Brown specialised in hurdle making.

The nearest school was the Elementary School in Wool. Until 1918, the school leaving age was thirteen, so any labourer born before 1905 would have finished with schooling at thirteen and immediately followed his father onto the land; but his children would remain at school until fourteen and have the opportunity to work for a scholarship to Dorchester Grammar School, leading to further education or even University. This fact, coupled with the widening of their horizons by five years of war travel, led to an increasing drift from the land and a very significant upward social shift. But in 1933 that was all of ten years away.

The working men did not have designer working clothes. Jeans were unknown. A man would buy a hard wearing dark suit for churchgoing, weddings and funerals, with a collarless flannel shirt and heavy black hob nail boots. When he could afford a new suit, the older one became his working clothes, to which he added leather gaiters over the trousers, and he wore the shirt without the removable collar but often with the stud in place. The more affluent farmers would pass on unwanted clothes to their workers; my mother was amused to see a man ploughing a field wearing my grandfather’s dinner jacket.

Village activities

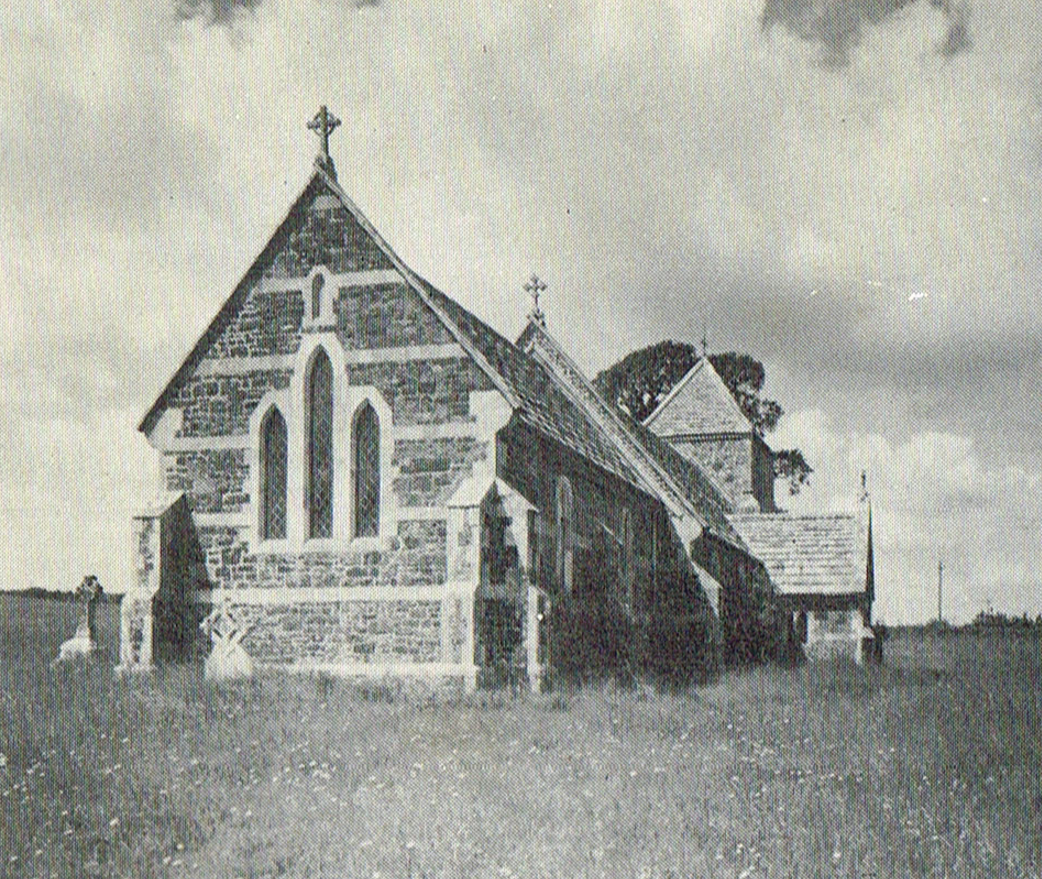

The social life of the village revolved mainly round the Church: choir and Sunday School. Most people attended, other than the Roman Catholics, who went to East Lulworth Chapel. The vicar, Rev. Phillips, came from East Lulworth, and he also preached at Tyneham, so he had a busy Sunday, and left most of the organisation and running of the Church to my family. His son, Peter Phillips, became Bishop of Portsmouth in the 1960s.

My mother set up a branch of the Women’s Institute, which was popular.

Whist Drives were very popular, when whole families would gather in the village hut or a large farm kitchen, four people to a table; and after each round of cards two people would move to the next table; the host would then announce “Hearts is Trumps” and off we went again.

We were too small a population to hold an effective Fete in the summer, so we joined with East Lulworth and held it in the vicarage garden there.

My family, with the help of the Squire, Joseph Weld, started the Lulworth Castle Hockey Club, using a field near the Castle. Not many villagers could afford hockey equipment so it tended to be mainly the farmers’ families who made up the team. We did quite well in the Dorset championships.

King George Vth’s Silver Jubilee in 1935 was organised by the Squire on the Castle lawn, with sporting contests and fancy dress competitions, and most of the Weld Estate villages were involved. Every child received a Jubilee mug. The same celebrations were organised for King George V1th’s Coronation in 1937. In addition, the Squire, Joseph Weld, donated an oak tree to every village. I watched Grandfer Matthews dig the hole for the tree on Coombe village green. He dug up a penny and declared that “this yer be rich zoil”. I am delighted to see (in 2014) how true that was, and what a magnificent oak tree we now have in Coombe.

In 1938, Dorset Women’s Institute held a Pageant at Lulworth Castle to celebrate Dorset History, from the Roman conquest of Maiden Castle to the 20th Century. Soldiers borrowed from Lulworth camp enjoyed being in Roman armour, and the young girls of Dorset delighted in being captured by them. Coombe, Wool, Bere Regis and Lulworth W.I.’s enacted the story of farmer Ben Jesty of Yetminster, developing vaccination against smallpox in 1774 using cowpox from local cows. Some Jesty descendants from Bere Regis took part.

The main hobby of Coombe women was knitting gloves, using wool issued to them by a buying company. Each finger required three needles. The knitters became so adept that they could knit without looking at the glove. They were paid eight pence per pair of gloves. They never knitted in Church, but otherwise they knitted everywhere, even during lectures at the W.I, with the speaker’s permission. A buyer would come round the villages twice a month, issue more wool and collect the gloves.

ARRIVAL OF “THE WIRELESS”.

Somewhere about 1934/35 a few people bought wireless sets into the village. As there was no mains electricity supply, and because the sets operated with thermionic valves, requiring significant power supply, these sets required 6 volt lead/acid batteries which were charged by a supplier in Weymouth and delivered round villages once a fortnight. I then delivered one such battery up the lane to an old man named Wilkes living in North Lodge, at the entrance to Lulworth Park; bringing the discharged battery back home, which I then swopped round when the battery man called the next fortnight. The experience of hearing a wide choice of music, talks, news and comedy shows widened people’s interests and subjects for conversation.

THE “ELECTRIC” ARRIVES.

In about 1936, overhead power cables were erected through the fields from Weymouth to Coombe, terminating at a transformer between the village and Church. I believe it may be the same one as is there today (2014). This had a huge impact on all our lives, once we were all connected up. No more candles or paraffin lamps; mains powered wireless sets; and for those few who could afford them, electric cookers and refrigerators. Other gadgets, such as electric kettles, vacuum cleaners, food mixers, and electric fires would have been regarded as unnecessary luxuries, and in any case, the small houses could not have room for them. There was still no water supply for operating washing machines.

The only complaint against electricity came from Granny Matthews, mother of seventeen children, when her bedroom was fitted with an electric light bulb immediately above her double bed. She told my mother “twern’t decent”, and continued to use candles, beside the bed.

WAR CLOUDS

In mid 1939, when war seemed inevitable, our village was briefed on preparations. The vicarage was selected as First Aid Post and Air Raid Precautions (ARP) centre. My mother was ARP co-ordinator. She and my younger sister had to collect gasmasks for the whole village by bicycle from Wareham; issue them , and give instructions how to use them.

We were ordered to dig air raid shelters. The best we could think of was to dig trenches in the field by the electricity transformer , modelled on WW1 zigzag trenches. They were never used, but they gave us the feeling we were doing something useful and later provided much fun for small boys to play in.

As the war was about to start, we were ordered to receive and house some thirty evacuees from London, mothers and children, from a train arriving at Wool next day. We commandeered West Farm house which was vacant (my father was temporarily running the farm), and also any spare bedrooms in the village.

The evacuees came from Lambeth. So far as we were concerned they could have come from outer space. We could not understand their cockney accent and they did not understand our Darset. There was a culture clash immediately. It seemed that, back home, they were used to meeting in their streets in the afternoon for socialising, in their best clothes, which seemed more suitable for the Hammersmith Palais than our village street, which was the only path for the cows, twice a day. Maybe the cockneys had never seen cow-muck before, but it certainly depressed them. One young woman came to blows with her landlady; so, within three days of their arrival they all descended on my mother with their suitcases packed and said they would rather face Hitler and his bombers than stay with us another day – so, off they went, back to Lambeth; everybody satisfied. A year later, Southampton docks were bombed and we had an influx of Hampshire children evacuees. They spoke with roughly the same accent as us and we all got along well.

By the time of the Dunkirk evacuation, in June, 1940, three of my brothers were in the Army and a sister nursing in the RAF, all overseas, a fourth brother joining the RAF, and my younger sister working in a shipyard. My father, then aged fifty-two, sent me to Dorchester Grammar School, and joined the Dorset Regiment as a private. My mother took on more voluntary work, with the Women’s Voluntary Services, the Women’s Land Army, as well as the Church and Women’s Institute.

This gave her good reason to cycle over a wide area of Purbeck. We were not aware that she had been recruited into the Auxiliary Units as a courier. This organisation had been set up secretly by the C-in-C, Home Forces, to provide local resistance groups in the event of German invasion. My mother, a teetotaller, would visit the Red Lion Pub at Winfrith where the public bar was divided up by curtains, so that she and others could talk freely, but without ever knowing who they were. She provided a message link from The Castle Inn, West Lulworth, (Mr. Downing) who used an Oxo tin in a tree stump near Coombe Church as a letter drop, which Mother passed on to the Wool Postmaster (Mr. N. Talbot) and onwards to a radio operator. Weapons dumps were under control of other volunteers who had received special training at Coleshill House, Swindon. I believe the nearest weapons dump to Coombe was in the woods to the East side of the Lulworth Road coming out of Wool. It was marked on a military map used by Google, in 2002.

Throughout the UK, towns and cities held an annual War Week, the aim being to raise money to buy a Spitfire or tank with the town’s name on it and give it to the War effort. It was also an excuse to have a bit of a carnival, stage mock air raids and gas attacks to keep the local population on their toes. I was caught out by a tear gas attack by the ARP in South Street, Dorchester, which proved to me how well my gas mask worked. One gas bomb ended up in Woolworths, and it was two weeks before the smell of teargas was cleared away. The poor shop girls had to work for two weeks with tears streaming down their faces. It was compulsory to carry a gas mask at all times, even to the seaside. Freestanding post boxes were painted on top with a special green paint which changed colour in the presence of mustard gas.

The first bomb attack we witnessed was on army buildings close to Lulworth Castle, by the gamekeeper’s cottage, in 1940. Two soldiers were killed. A few months later, Coombe was bombed. Not a cow or house was hit, and I am sure the German pilot was simply dumping the bombs randomly on his way home after being damaged. These were incendiary bombs, about eighteen inches long , and they scattered across the fields as far as Wool. Many landed in soft ground and did not ignite. We were able to dismantle these to see how they were constructed.

On one summer’s day we witnessed one massive fleet of bombers high overhead, heading inland, with vapour trails. We saw fighter planes come to meet them, and soon the sky was covered in swirls of vapour. We went inside and then heard swishing noises as spent bullets fell into the churchyard.

As the War proceeded, the population of Coombe fluctuated, mainly due to the pressure on accommodation caused by the Military and their families. At the Vicarage we had Privates and Majors and their families squeezed into any spare room, including the conservatory. They came from all over the UK, and gradually widened the interests of the village.

Petrol was rationed and only issued for essential use, so private cars were rarely seen. Bicycles were used regularly to travel as far as Weymouth or Wareham. Trains were rarely on time and were usually overflowing with soldiers. There was total blackout at night, making night travel hazardous.

Food rationing was adequate in Coombe, because most of us kept chickens. My mother bred rabbits, which we penned out in the churchyard to keep the grass down. We searched the hedgerows every day for cow parsley, which the rabbits loved; and this gave my mother an opportunity to look for messages in the Oxo tin. We sold the rabbits to a butcher.

Church attendance fell off significantly at this time, due to long working hours, allotments to attend, and a floating population. There was no longer a choir nor Sunday School.

After the victory in North Africa a large prison camp for Italian POW’s was set up in the car park at Lulworth Cove. They were being used to widen the road into Bovington Camp. They were a happy-go-lucky lot, enjoying the peace and tranquillity of Lulworth without tourists or Germans. When they were not working on the road they were either playing non-stop football in the field next to Lulworth Church, racing boxes on pram wheels down the steep road to the Cove, or paddling rubber boats in the Cove. Clearly, none of them wished to escape anywhere, least of all, to France. I would cycle to the Cove for a swim and perhaps chat up one of the girls on the beach. Not a chance. Having shown my Identity Card to the guard by the tank traps at the entrance, I would find all the girls fully entertained by these handsome Latinos.

Coombe was not affected by the American invasion. They were more concentrated in Weymouth.

Immediately after D-day the countryside was quiet. Most military traffic was in France, and there was no private traffic. Any vehicle that was on the road would stop and pick up hitch-hikers, and this was quite a normal method of country travel.

POST WAR

After the war ended in Europe, May, 1945, servicemen and women started drifting back to the village, just as I was about to leave, to join the Merchant Navy, attached to the British Pacific Fleet.

The dropping of the atom bomb on 6th August 1945 kept me out of hostilities. Instead, I spent the next two years following the Fleet in the occupation of Hong Kong, Japan and Shanghai; so I did not meet some of my family for five years in all; and I cannot comment on the transition of Coombe from wartime to peacetime. What I did notice, when I returned, in 1947, two years later, was the change in attitude among the younger people of the village. There was more self confidence and ambition than in pre-war times; and they were less inclined simply to follow Dad onto the land. They were all required to spend about eighteen months doing National Service, much of it overseas, and their horizons were widened.

Over the following years, with the ending of petrol rationing, bicycles were replaced by motor bikes, and even a few old banger cars started appearing. The Church attendance suffered; the choir and Sunday School long since gone, and only a few of the older congregation turned up to the Sunday service. Weddings, baptisms and funerals continued as before. My sister Mary, an RAF nurse, was married in Coombe in 1947, and I married my wife, Beryl, in July 1955. At least five of our extended family children were baptised there over the next few years. One baby, who died at birth, is buried to one side of the Church porch.

Whenever I returned from long voyages for home leave, I would notice the changes in Coombe. When the dairy closed, the village street was cleaner; somebody cleaned up the dirty pond and made it attractive; TV aerials started sprouting above the thatch; the oak tree looked bigger. Telephones appeared, and cottages were being occupied by non-agricultural workers.

Coombe Keynes Vicarage was a wonderful home to bring up a large, extending family. In pre-war times my elder brothers and sisters tended to bring home school friends for the summer holidays; so my mother set up three tents on the lawn to house them all. All the boys had guns, so we fed our guests on an endless diet of rabbit stew. In post war times we filled the house with our own children.

By 1967, my parents felt they could no longer cope with the house, chickens and garden; so they moved to a bungalow on Ballard Down, Swanage, which my generation still owns.

It was with great pleasure that my sister Susan (90) and I (86) with my wife Beryl and two sons, all visited Coombe Keynes for the Open Day on 22nd June 2014; to talk with Coombe residents about the past and present, and the beautiful way Coombe has been preserved, yet developed into such an attractive residential village; and to pay homage to the memorial in the Church to my two brothers who did not return.

Michael Drew – July, 2014.

Photos of: Drew War memorials

Wife Beryl married in Coombe in 1955 / the Vicarage / photos of Granny Matthews complaining about the electric